A (very brief) History of Jazz and Church

A discussion on the interaction of liturgy and music is usually off to a good start with looking at the reflections on music by the early church father Saint Augustine of Hippo. Augustine´s complex relationship to music started during his Christian conversion. The singing of hymns always had a deep emotional impact on him, but he struggled in his writings with a conflict of how much free musical expression was allowed within worship. Augustine considered it a grievous sin when the music used for worship brought more enjoyment than the words it conveyed.

Suspicions were also raised fifteen centuries later when Jazz was used for worship. The earliest document I found dates back to the year 1929 and is a report of the speech of the Church and Organ Congress in Hull (UK) where Sir Hamilton Harty, the, president of the Incorporated Association of Organists spoke on “Some Problems of Modern music‘ and warned, that ‘Jazz Barbarians were permitted to debase our music.’” One of these Jazz musicians, Louis Armstrong had started to play Hymns, Spirituals and Gospel tunes in the new style of music that was later called Chicago Jazz.

A church musician whom the Incorporated Association of Organists treasured and in some ways owed much of their existence to, Michael Praetorius, would have thought probably very different about the importance of jazz for worship. Praetorius followed Martin Luther’s view that “music is next (like a sibling) to theology” and essential in biblical teaching and understanding. In his own body of compositions, more a thousand works overall, Praetorius made use of all the instruments and styles available for him in his time, and used compositional techniques and instruments from the court and the chapel alike. To him music inside and outside of churches could be sacred, heavenly and earthly sounds could be in unified resonance; sounding Soli Deo Gloria and pointing towards a celestial sonic experience as a glimpse of God´s eternity. It can be assumed that Praetorius, if he had had a chance to listen to Louis Armstrong and John Coltrane, would have loved to include them and their sounds in this heavenly orchestra.

20th century definitions of sacred music struggled with this all embracing view. The gap between the seemingly profane (or secular) and concert music and the established canon of church music, which was considered to be sacred music per se, had grown bigger and more and more a disconnect between the musical styles and aesthetics heard inside and outside of churches was created. Theologians and liturgy scholars across denominations became interested in embracing contemporary classical and popular music within worship services. These developments coincided with an interest from musicians and pastors alike to create Jazz Vespers in Churches in the USA and Europe from the 1950s onwards.

Jazz in the USA had arrived to become accepted as “American Classical Music”, a term that both Gospel composer and Billy Taylor and George Gershwin had tried to establish over several decades and became an ideal catalyst and bridge builder between the secular and sacred. Jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis points out, that Jazz is a music between “heaven and earth”, between the church and the night club, if you take one of them away, it looses it´s meaning. His brother, saxophonist and composer Branford Marsalis remembers that churches in the southern states of the USA where naturally involved in creating cross-connections between sacred and public spaces by simply having to open their windows all throughout the spring and summer to the heat. The Sounds of the gospel band and choir rehearsals and the church services could be heard all over the town and every musician in the south grew up with them. Additionally many jazz and blues musicians who worked in nightclubs and wrote theatre music where employed as worship leaders and church music directors in African American churches. Thomas Dorsey, one of the most influential composers of Gospel music while still working in nightclubs hired singers like Mahalia Jackson and Della Reese who sang along Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. Jazz went to church and became an important timbre of church music during the classical era of Swing and Big Band Music all over the USA.

After World War II when Avantgarde Jazz, Be Bop, was performed in Symphony Halls, a new consciousness for the spiritual dimension of jazz arose within the jazz community. George Lewis and his Ragtime Band produced the first record of hymns in jazz arrangements in 1954, „Jazz at the Vespers“. Tenor saxophonist Ed Summerlin and his Contemporary Jazz Ensemble toured University Campuses and Churches all over the USA after the success of his broadcasted Requiem for Mary Jo (NBC-TV) and his 1959 record entitled “Liturgical Jazz”.

This critically acclaimed jazz setting of a morning service based on the book of common prayer marks the beginning of the tradition of Liturgical Jazz.

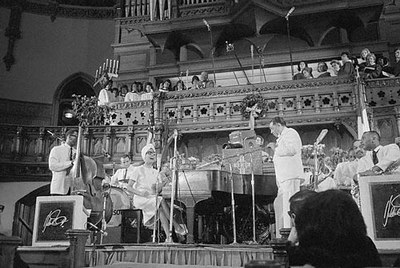

At the Lutheran Saint Peter´s Church in NYC the first jazz ministry started in 1965 as an initiative of Reverend John Garcia Gensel. This ministry is still active today with weekly jazz vespers, midday jazz concerts and several community jazz festivals. In 1965 Duke Ellington’s first Sacred Concert premiered at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco before an audience of 2500 people and was filmed for local television. Besides its mixed reviews and surrounding controversy (including death threats to local priests), it undisputedly counts today as the initial artistic event that combined contemporary jazz and liturgy in a concert setting and gave birth to the tradition of Sacred Jazz.

Earlier in 1965, tenor saxophonist John Coltrane released his album “A Love Supreme”, based on his 1957 spiritual awakening, which became next to Miles Davis´ ”Kind of Blue” one of the best selling jazz records of all time. In his detailed analysis of both the studio recording and the live recording of “A Love Supreme”, Lewis Porter points out, how organically extra musical meaning is integrated in Coltranes improvisatory language. Porter demonstrates, that Coltrane´s compositional outline, “To say thank you to God” is fulfilled with re-enacting chanting and formal structures of his own biographical background from his upbringing in the American Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (his two grandfathers were ministers). “A Love Supreme” is pivotal for an entire movement in jazz that is often referred to as Spiritual Jazz, an (often interreligious) universal praise of God through jazz.

Contemporary Artists with Christian background, such as Brian Blade, Tord Gustavsen, Ike Sturm, Bobby McFerrin, Jon Cowherd, Kirk Whalum and Kurt Elling continue these traditions of Liturgical, Sacred and Spiritual Jazz, and their music can be seen as modern counterparts of Michael Praetorius and contemporary composers of sacred music, incorporating all earthly sounds to imagine heaven, all pointing towards a celestial sonic expression of a unified SOLI DEO GLORIA, be it in the church, the concert hall or the jazz club.